Thursday, February 29, 2024

How to stay alive traveling or commuting by bicycle

How to stay alive traveling by bicycle

Lessons from the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route (My personal experiences and solutions)

Bikepacking School with Bill Poindexter is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Authors note: Much of this information relevant to all travel by bicycle, survivalists and backpacking as well. It is primarily intended for novices, but I believe the experienced folks will enjoy it as well.

Introduction: Understanding situational awareness and cause-and-effect:

Situational awareness and understanding cause-and-effect is paramount to surviving any long journey. Knowing where you are and what’s around you and then taking the appropriate action to navigate through that environment or situation will keep you alive, hopefully. It all depends on your skill set, grit, and knowledge as well.

Common sense is needed as well. A good example of situational awareness is riding from one destination to another in the middle of a rainstorm when the temperatures are between 35f and 55f. Knowing your gear and limitations, and where possible shelters are on route. And also having the understanding of cause-and-effect that if you keep riding in that weather, eventually you could get a hyperthermic and have to call for rescue which could put the lives of other people in danger. So maybe in this situation it would be better to stop and camp and get under some shelter versus continue. Or, if able to find some commercial shelter, and wait out the weather. I will talk more about this later.

Another example is cycling through bear country, especially in Montana, making sure that you are making noise, “HEY BEAR”, especially at turns in the road, so you don’t come around the corner, coming off of downhill at high speed and bumping into a grizzly bear with cubs. I’ve seen too many people on FB with pictures of grizzly bears that were fairly close to their proximity, that only tells me that they weren’t being properly noisy on route.

Situational awareness and cause-and-effect is very important here… Because if you get attacked by the grizzly bear, the grizzly bear will be euthanized. End of story. Other examples I have are people that did not state properly hydrated and ended up having to be rescued, and others who are just unrealistic on goals.

There’s more that I’ll talk about in my next podcast on the subject. But I think you get the idea.

Invisibility

The number one thing I teach in bicycle safety courses is to have the consistent mindset, while riding, that you are invisible. I know that on the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route (GDMBR) much of the time you’re in areas where there’s very little traffic but even then, it’s good to stay vigilant and make sure that people can see you and they know you’re there. There are times when you have to bike through urban areas where traffic can be fairly heavy or in resort areas like Breckenridge, and in those times, one should have flashing lights and make sure they obey the street laws that you are a vehicle yourself. I know of at least one person who was hit from behind and killed on a New Mexico Highway in 2019. I don’t know the circumstances, but I do know from riding numerous highways myself heavily trafficked that it’s super important to be on whatever shoulders available and have flashing lights and also a good they have a rearview mirror to know there are vehicles coming, so one can ditch. It’s also important to know that in times of early morning or late afternoon that makes people harder to see as well because of bright or low-level light. Additionally, coming to turns or cresting hills can be dangerous. So, if you want to stay alive, and I’ve ridden my bike for 24 years commuting, full-time and doing my long-distance journeys and I’ve never been hit by a car because I assume I’m invisible and you should always do the same.

Bear country tactics (and other wildlife)

The first time that I rode part of the GDMBR. I flew into Missoula Montana and rode my bike over to Seeley Lake, MT to connect with the Divide. I stayed at the campground in Seeley Lakes, there was an ex national park ranger who used to live in Alaska, and he asked me if I was carrying bear spray and I told him I didn’t think I needed it and he proceeded to explain why I did need it. He shared a story of a man who was killed by a bear because the bear was surprised by the man who ran into it on a turn, a sad ending for the man then Fish and Game came to euthanize- the bear so I went and bought some bear spray.

Last summer, I based myself out of Polebridge, Montana in between the Flathead National Forest and Glacier National Park just 20 miles from the Canadian border. The Saloon I worked at had us go through bear training through the Glacier Institute where we actually were taught how to use bear spray by using inert bear spray. It’s important to go through that training and the two biggest things I learned was that you want to carry the bear spray on your body because if you get separated from the bicycle and the bear spray is on the bicycle, then it makes for even more of a dangerous situation. One can attach it to the strap of a Camelback, hip belt, or small backpack, and there are also companies that sell bear spray holsters that are strapped to your chest. The instructors told me about an incident, where a young woman had the bear spray attached to her chest strap on her Camelback and had come around the corner and surprised a grizzly, and she fell off the bike trying to stop and was on the ground as the surprised grizzly charged her. She was able to reach up to the strap and unclip the safety and expel the spray still in the holster, driving off the bear -not an ideal circumstance, but it did save her life. Another thing to that I took away from the class is how to spray the bear spray- is that if a bear is coming to you (mountain lion, moose, dog, wolf, anything that is about to attack you) with a charge, you spray it from hip to hip and a half circle basically at hip level, so whatever animals coming to you, they get into the cloud of the spray and it will immediately deter them. They recommend you carry two canisters, for obvious reasons. And do not accept old canisters as they can fail. Oh, and hang your food or buy a bear canister and don’t keep food in your tent!

Water purification

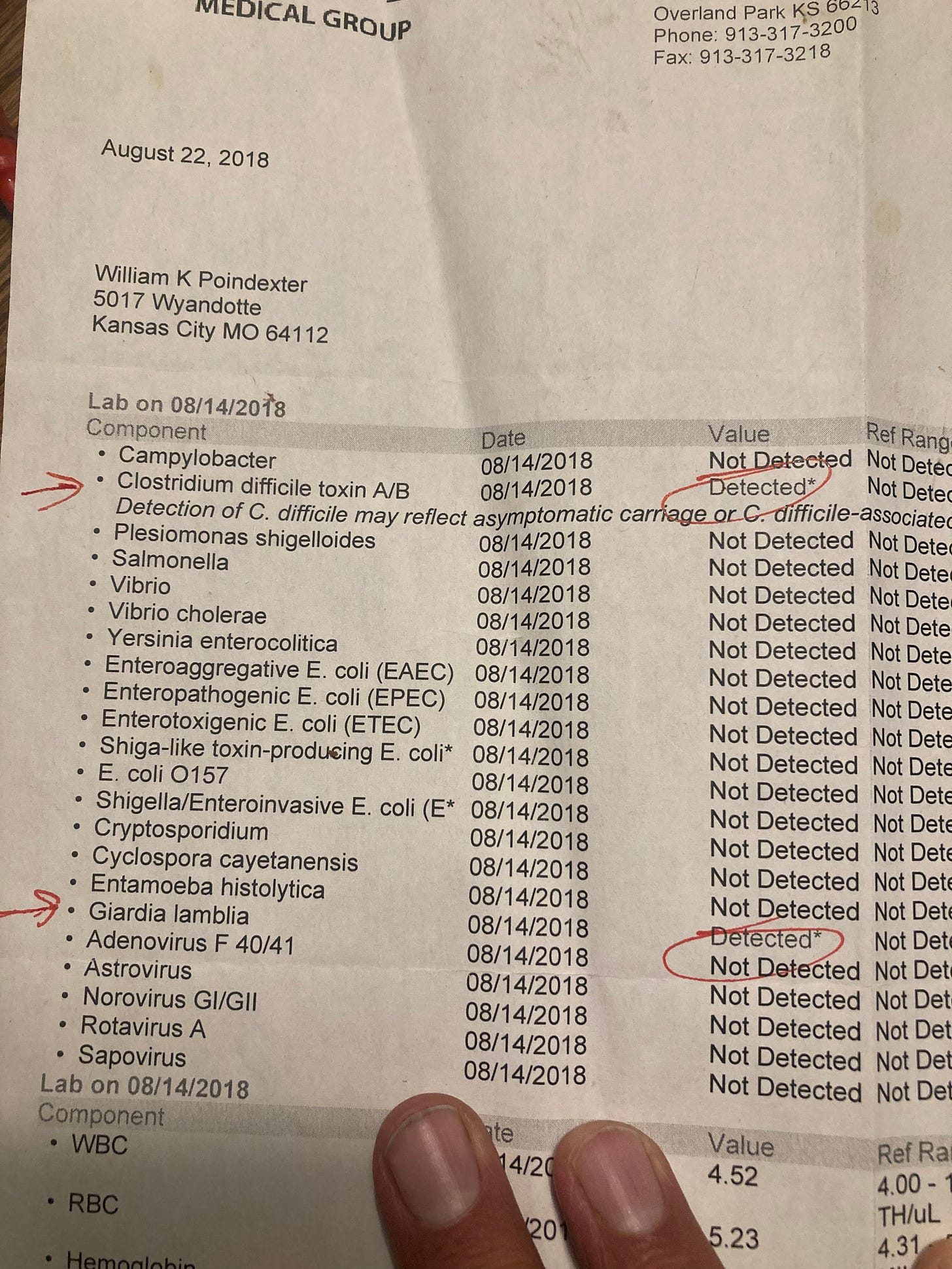

The last time I was on the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route. I ended up getting Giardia and some other nasty parasites that affected me for almost 2 years afterwards.

Even caused me to poop my pants while I was on the Divide- you can read about it in my book, Bikepacking School- What ‘they’ don’t tell you in the guidebooks-available on Amazon. And I was using two forms of water purification, a Steripen and chlorine tablets. The Giardia was never really bad when I was on the Divide with the exception of the pooping accident and that could have been a combination of things-stress, bad water, a greasy hot dog. But when I got home, I really felt the effects. My contention, based on my experience, is that no water purification is completely safe. And also on the Divide, there are many places where there’s agriculture and the use of insecticides, fertilizers, poisoned water sources from mining as well as many high places in the high country where there is grazing for animals, and that runoff is in the water supply. There are a few exceptions. But I’ve also come to the conclusion that it’s almost better to just drink water directly out of a source, then try to purify it. I know this is controversial and there are exceptions to that. But unless you are just totally anal and wipe off any excess water on containers that you purify and don’t swim in streams, then chances are you’re somewhat at risk. I know riders who drink out of streams and rivers, and creeks on a regular basis. As long as I am below a town or pasture, I would try to drink bottled water or even ask locals if I can refill. And I also know riders who will only buy bottled water. And I’ve known a lot of through hikers on, like the continental divide trail who say they end up getting diarrhea anyway. I myself have done a lot of backpacking and I usually have a bout or two of diarrhea at the very least even with regular water purification. I am not going to plug any products, do your own research. This past summer I drank out of lakes and streams in remote Montana, and never had any problems.

I do have questions about some of the water purification companies to like, for instance, the trip where I got Giardia. I was using a Steripen, which says it kills everything because of the use of ultraviolet light? But doesn’t ultraviolet light come from the sun? And they talk about how the UL kills viruses but yet viruses are believed to be from dead tissue-because to date no one has ever been able to show us a “living” virus-which begs an even larger question 'how do you kill something that is not alive?’ And how could something so small that can only be detected by an electron microscope be filtered? And one has to wonder if the reality narratives we, as humans, are being told, are indeed false. False by ignorance or blatant lies. Do your own research. I can speak of this as I was very cautious but still got sick. This is a good article citing a study out of the Sudan and here is a good book that will give you more insight on water borne parasites.

If you think you're compromised you should on a regular basis use electrolyte mix as well, there are many out there, just practice with them so you know it won’t upset your tummy. Most water is sterile and your body needs the salts, and minerals when spending long days in the saddle and those mixes will help you avoid bonking- I have been on two trips with people who bonked severely and had to be helped-to recover, they were completely irrational, ranting, messes. I got food and water in them and stayed with them until they were coherent and themselves again. Fuel up! If you are solo and bonk severely you can make a bad decision and crash.

Staying safe, camping strategies

I always prefer camping out either setting up my tent or just sleeping cowboy style on the ground just my pad and sleeping bag. And although I do welcome the occasional campground with showers and other folks, I usually prefer to stealth camp. I once rode with a Chinese guy who claimed he rode all the way from New York City to Baja California, where I met him, and never paid to camp. While camping, unless in bear country, there are two things I worry about. That I’m well hidden from human eyes, and I make no impact on the environment, well as little as possible. In all seriousness, it’s the the wildlife, you really have to be leery of, not the animals, unless you’re in beer country and you were foolhardy enough to leave a bunch of smelly food in your tent, now the type I’m talking about is the wild humans. One really has to use common sense. It’s important to memorize the no trace camping principles- I’ve been mortified by all the places I’ve been to in the United States all over the United States where people camped and they left behind trash and toilet paper, and I’ve been to some pretty remote areas. Being safe camping also means camping smart too. You can be harmed by an inanimate object like a tree falling or a branch falling from a tree. I’ve seen a lot of how-to videos from newbie Bikepackers, and experienced, who set up their tents right under trees that look pretty sketchy.

And when stealth camping- as long as you start camping at around dusk, and leave at first you can camp anywhere, within reason, without having to ask for permission if it’s not public land, most people won’t begrudge you a place to sleep especially if they’re close to the route. Go with your gut instinct, and if it feels wrong, move on.

Bumps in the road

I don’t have very many fears when I’m on the road, but I do like to make sure I err on the side of caution. Sometimes there’s a lot of bumps, debris, litter, on the road and it’s always important to keep your line as you ride. And it’s always important to stay in the moment as much as you can. It's easy to get distracted with thoughts and maybe look at the scenery. And I have this issue whether I’m in the city commuting for bikepacking on expeditions. There’s always bumps in the roads or holes on the roads. It’s just an evitable and it’s important to know where they are so you can avoid them otherwise you can have a catastrophe that could possibly end your expedition. One of the biggest things I learned on the great divide mountain bike route was that when you’re on a downhill and the roads rough and it’s either early morning or late afternoon and the roads surrounded by trees, there can be lots of shadows from those trees that make the road look dark in some places and light and other places, and it’s hard to tell the difference between a shadow and a rock, so it’s probably a good idea to take it slow.

Bike failure

This past summer I was based out of Polebridge Montana. I was working out of the saloon there, and I took my surly bridge club. That was basically only three months old and did a lot of bikepacking trips, mostly bike overnights in that area in Glacier National Park also into the Flathead National Forest and up GDMBR as well. For some reason the bike I had was jinxed, I had issues with the crank arm coming off five times and I managed to put it back on, but it was a pain.

And later in the season, I was cleaning my rear wheel, and I noticed there were cracks in the rim on eight different places where spoke entered the rim. There was a total of 23 cracks, it was the WTB rim which came with the bike. I ended up replacing the rims, but I was definitely aggravated that I had to do that. Later on, I went to Glacier Cyclery in Whitefish, MT, and they told me that there were a lot of Divide riders that came in with the same issues. I’m not sure why wheel manufacturers would make such a product. And then I was equally aggravated at surly bikes for promoting that bike as the ultimate Bikepacking bike and having such a crappy wheel I mean; don’t they test the wheels? I’m just glad it didn’t fail on me when I was doing a trip. I also found that using simpler bikes versus sometimes better than a high dollar one. In 2018 I rode my Salsa Cutthroat from New Mexico to Banff and had more issues than I ever had with any of my other bikes. Then after the divide, I used it on a few bikepacking trips in Kansas, Missouri and Colorado and I used it as a commuter bike as well and two years later I was going to sell it and found out the top tube had two cracks in it. Salsa claimed it was my fault because I didn’t clean the top properly but that could’ve been a disaster as well. Keeping your bike well maintained and checking it over every day can perhaps avert a disaster. I have had a pedal come off that caused me to crash, and a chain issue that caused a crash as well. I was riding with a friend of mine on a very rough gravel road, he got his wheel stuck in a deep rut, tried to turn his handlebars to get out of it, but the handlebars were loose, and as he turned the bars, the bars moved but the wheel did not turn, and he crash landing his 240lbs body on the handlebars. He broke six ribs, and punctured a lung, it was a good thing I was with him to preform first aid and call for help.

Weather and self-rescue 101

When I was 16 years old, I was the head medic at Military School. I remember having to treat Cadets with heat exhaustion and heat stroke on an overnight bivouac after hiking through dense woods by the Missouri River in 95f+ heat and high humidity. I had to treat myself for heat exhaustion as well, I remember thinking I never wanted to go through that again. Just a few weeks after that I had to split a football player's broken leg on the sidelines. I learned first aid at a young age, and the need to be able to self-rescue as well.

I commute at least 300 days a year, and all types of weather and when I’m home I make sure that I test gear throughout the year and when there’s opportunities to go out and get wet and cold and try new gear out, same with the heat, I take advantage of that because I’m in a controlled environment. On a regular basis I even do long hike and bikes, fully loaded, just to stay strong. I understand hypothermia and I understand heat exhaustion and heat stroke, I know the signs, how to treat and I know how to avoid it. So, I do avoid it. And I’m amazed at the stories I hear of people getting rescued off the great divide mountain bike route because they’re hypothermic. So, I guess it comes from my mountaineering background that I know that if it’s a situation where you could possibly get hypothermia and then you set up your shelter and get into your warm sleeping bag, eat, and heat up a drink if you have a stove. And I know people take lightweight shelters, bivy bags. I personally think people should have to take tents instead of bivy bags so they can stop and set up and wait for the storm to pass if needed, so they don’t have to put other people at risk having to be rescued. They become self-rescued, which is something that I think all Bikepacker‘s needs to take courses on. Maybe I’ll make a course for it.

I think too many people rely on the rescue buttons on Spot trackers versus using good sense. It wasn't that long ago when there were no cell phones or satellite tracking devices. It’s cause-and-effect. Consider this, what if you get cold or hyperthermic and you have to call for rescue in the middle of the night and a helicopter is dispatched, but the helicopter crashes and kills a crew because of your mistake? That’s not good. I interviewed a woman in 2018 who rode through New Mexico during one of the hottest years and she was found on the side of the road unconscious and had to be in the hospital for two days before she continued riding. She was 69 years old at that time and turned 70 by the end of the trip. I understand pushing your limits and one can do it smartly.

The first time I was bicycle touring the GDMBR I flew into Missoula I was dealing with multiple non serious injuries: Afib, winged scapula, sciatica, old neck injuries that occasional cause vertigo, depression and anxiety-but was not on any medications (by the way know what the possible side effects of medications or recommended travel preventive vaccines are before you head out on the road, so you are not surprised.) I knew how to manage my stuff through Yoga, rest, and breathwork.

Anyway, when I flew into Missoula, I had just gotten off the plane and met a Tour Divide rider who had to scratch (take himself out of the race) and was heading home. It was 2017, a cold and rainy year. He had pushed himself too hard and his Afib caused him to quit after a visit to the emergency room. Since I have Afib as well, it scared me a bit, was not what I wanted to hear just off the plane- but I went on my 21-day journey anyway…a story I will share soon.

A good dose of common sense, experience, training, and preventative measures can keep you alive on adventures like the GDMBR.

I think solutions can be doing a lot of training before you go out on the ride and that training can be just commuting by bicycle, being in touch with your bike, your body, your mind. And how everything works in all different types of weather throughout the year. I know you can’t predict everything and sometimes circumstance and fate will put you in unpleasant situations, but what you can do as a Bikepacker is be prepared as possible.

And that brings me to one thing I should’ve brought up earlier I’ll just bring it up now- is make sure you have strong wheels and make sure before you go on a bike packing trip that a couple weeks before hand, if you need to replace your chain then replace your cassette, have your brakes bled if you need to check your brake pads. Also do a full inspection of your bike especially if you’re on a carbon fiber bike, check the bike internally for cracks if possible. Also, my last thing and I want this one to go to heart more than any of the others.

Sidenote, to all you who travel by bicycle, you are the explorers of the 21st-century, you have many character traits that are similar to the explorers of past. I will write about this soon, so stay tuned.

Remember while riding your bike, you’re invisible. Be safe my friend.

Peace and love, Bill Poindexter

Please support my writing!

About the author:

Bill Poindexter is an American writer, based out of Kansas City, MO, USA.

Bill has traveled over 100,000 miles over the last 24 years, commuting and traveling.

For more info and some of his writing go to

wholeearthguide.blogspot.com

more useful information coming soon!